My Regards to Bint Jbeil

She Who Defended Her Honor*

By Marwa Elnaggar

By Marwa Elnaggar

Would you like to see a bomb?" Kefah asked us, leading us to a house half-damaged by Israeli rocket-fire. When I had written in the summer of 2006 about dreaming of returning to the South of Lebanon, I never imagined that I would be back so soon. I had also never imagined that I would be carefully stepping over rubble, placing my feet where the Hizbullah fighter leading the way was placing his feet, at the risk of becoming a post-war casualty of unexploded ordnance

It was noon on a sunny Friday in December 2006 when we arrived in Bint Jbeil, referred to by Hizbullah and the people of the South as the capital of resistance and freedom. Until the moment we saw the road sign simply saying "Bint Jbeil" and pointing straight ahead, the town had retained an almost mythical existence in our minds

According to our maps, Bint Jbeil lies less than 4 kilometers from the border between Lebanon and Israel, or, as everyone in the South called it, Palestine. For a long while, for more than a year, the town had remained a dot on our maps, unreal, subject to the wild twists of our imaginations

Our only brush with Bint Jbeil had been references made by Hizbullah's resistance fighters before the 2006 war, and during the war, constant news mentioning the situation in that mountain town. We heard the news throughout July and August of 2006 and stared for hours at that spot on our maps in Cairo, trying hard to imagine the people there, the houses, the battles. Geographically, it was so close to Egypt, but for all practical purposes, it was so far away

Passing the road sign and entering the town, we felt a sense of unreality. It was hard to believe that we had finally arrived. The realization that we were now inside that map that we had stared at for so long came only after we had left it

They Are No Longer Streets

The roads leading to the south of Lebanon are a testimony to the men who had fought Israeli occupation in the latter quarter of the 20th century and more recently, those who had died in the latest war in the summer of 2006. Their pictures are stuck on walls, and on lamp posts, and are strung above streets. Resistance fighters who had given their lives for the freedom of their lands are glorified throughout the South

You can not walk into any Shia majority town as close to the border as Bint Jbeil is and not be attacked by scenes of destruction. We had seen the ruins of the Southern District of Beirut earlier that week, but in the South, the effects of the war took on a whole new meaning

The streets were no longer streets in Bint Jbeil. Littered with the dust of vaporized rocks and the sad leftovers of vicious attacks on the town, many of the streets present a challenge to cars and trucks, making walking the best form of transportation

Walking, however, brought us face to face with the devastation. Bint Jbeil is an old town; its name roughly translates as "Daughter of the Mountains". The streets we walked through were narrow, steep, and twisted

This was not a modern, geometrically planned town, but one in which the spirit of an older, slower, and rustic way of life still hung in the air, competing with the faint acrid smell of modern, man-made dust and death

Vast sections of the town were buried under the rubble of the houses. Entire neighborhoods were obliterated, the spaces that defined individual houses, gardens, and courtyards violated, the borders between them erased

Come See Where We Hid

War, we discovered, does not only kill people and destroy houses. Walking in Bint Jbeil, and talking to its people, we realized that the war also sought to annihilate an entire social fabric and heritage

We met two women with a young boy and a baby in a neighborhood that was utterly destroyed, apparently visiting what used to be their house. As with all the people of the South, their immediate reaction when they saw us was a warm welcome, and an eagerness to tell us their story

Would you like to see our house?" one of the women asked, taking us to a pile of rubble. She pointed to an open space between several destroyed homes

All the neighbors would sit, talk and drink tea or coffee together every afternoon here in this courtyard," she said, naming the families of all the houses surrounding the courtyard. "This is what I miss the most. We yearn for these gatherings

She fell silent, her eyes resting on the wasteland that once teemed with love and life, remembering her neighbors, some of them dead, all of them homeless

These traditional gatherings of the local community were one of the major victims of this latest war. The social cohesion and solidarity that had been passed on from generation to generation over the centuries was now at risk. The homes and the courtyards symbolized an entire heritage that was being wiped out

Coming from a country that had witnessed war first-hand and had suffered from the aftermath of peace with Israel and American hegemony, we were scared for the future of the idyllic villages and towns of southern Lebanon

Shall I show you where we hid during the war?" the woman asked. They, along with many others had been trapped in Bint Jbeil for a while. We had to duck as she led us to an underground hideout, no bigger than 24 square meters, its ceiling too low for anyone over 5 feet to stand up straight in. Plastic straw mats and dampened pillows lay on the ground

There were 42 of us. We stayed here for 15 days

She showed us another, smaller "room" reminiscent of the solitary confinement cells of the Khiam Detention and Interrogation camp. "We couldn't go out at all. We stayed here, slept here, went to the bathroom here, everything

I'm sorry it smells so bad, but it's so damp here." The air was stifling, humid, and musty. We could hardly bear to stay there for long and breathed deeply the fresher mountain air outside the hideout

We really had nothing to eat," she continued her story. "For 15 days we starved. We only had sugar and semolina

We Remember What We Bombed

We Remember What We Bombed

The two women excused themselves and went on their way. We stood in silence, staring at their backs as they walked to wherever their "home" now was

Many times in the South, we found ourselves speechless. No words could ever describe what we saw, what we heard, and what we smelled. It was the closest either of us had ever gotten to war, and it was beyond anything we had ever imagined

While we were standing there, a man zoomed up to us on a scooter. "Welcome," he said. "My sister just met me and told me about you. She said you wanted to hear about the war. I can tell you. I was here. I was one of the fighters

The woman we had been talking to was this man's sister. His name was Kefah, he was one of the 40 Hizbullah men who fought in Bint Jbeil

These men were legendary. Hizbullah commanders had designated three lines of defense, instructing their fighters to leave the first and second lines when they felt Israeli pressure. The fighters surprised everyone, including their own commanders, by not giving up a single line of defense

Kefah was part of the legend, but the only thing about him that suggested this was his build. He was tall and bulky, his face reddened by the sun, but without the half-shaven beard so common to Hizbullah members. His entire demeanor, his calm voice, his friendliness, suggested nothing of the fierce fighter he was

He gave us a short tour, showing us an old cinema house that looked more like a world heritage site despite the rubble than anything else. The cinema house had been built most probably in the first half of the 20th century. Its walls were of stone rather than brick, like those of many of the houses in Bint Jbeil

Across what used to be the cinema, he led us into another house. We didn't think of any apparent danger as he lifted a red and white plastic ribbon surrounding the house — what should have sent any existing warning bells in our minds ringing — and entered; we just followed. "This is my brother's house." Like everyone in the South, he had his own stories to tell about the war

Everyone told me "Praise Allah for your safety" after the war finished. Me, I'm thinking, "For what?" I didn't want to stay alive." His honey-colored eyes were intense

I would rather die a martyr than die some natural death." This was a recurring theme we heard in the South. Many people expressed the sentiment of preferring death by martyrdom. The idea of sacrificing everything for the sake of the freedom of your people and land was very much alive in the minds of everyone we met

Look at that building over there," Standing in what might have been a balcony or a living room, he pointed at a building that was half-destroyed by the war. The right side of the building had been destroyed by an Israeli rocket attack in the previous war, but its owner had rebuilt it

They remember. They know which side they hit. This time they hit the other side

That Teddy Bear Is a Bomb

When Kefah offered to show us an unexploded bomb, we weren't really thinking, but eagerly followed him to the roof of the house. He pointed to a small, innocuous looking canister, no bigger than a mobile phone, lying in wait underneath a water tank

This was just one of more than a million bomblets scattered by Israeli cluster bombs throughout the 33 days of the war in 2006, according to a UN report. They can be found in the rubble of houses or fields of olive groves

These bomblets, we later learned, came in all shapes and sizes. Some looked like conventional mines, while others were disguised as rocks or even toys

Bombs like toys… the irony is bitter. Governments that wage war on children deal with the entire concept of war as if it was a game in itself. What kind of mind would create a bomb in the shape of a teddy bear

Before Kefah left us, he invited us to his home. "My house is very close by. I would be honored to have you come for tea." Although the idea of having tea with a fighter appealed to us, we had to apologize, as we had been invited to so many homes and had met with such hospitality that it was getting embarrassing

If you change your minds, you are more than welcome to come at any time." He got on his scooter and zoomed off

The Grandfathers of Our Grandfathers

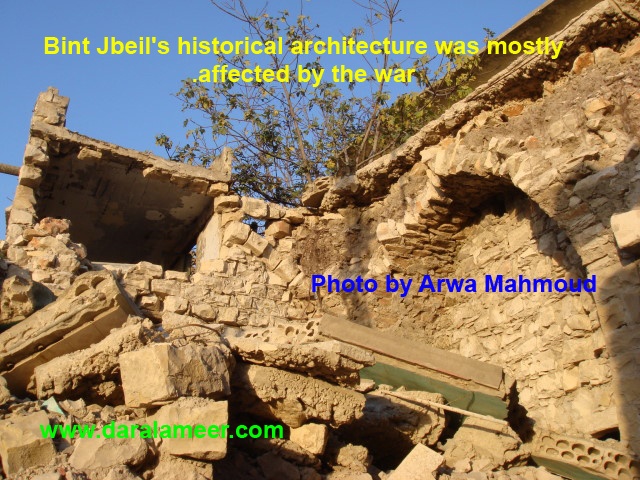

One of the most distinct features of Bint Jbeil are it s old houses and narrow winding streets. The archways of houses and the doors and windows all speak of a heritage now buried under ruins

s old houses and narrow winding streets. The archways of houses and the doors and windows all speak of a heritage now buried under ruins

Standing among the ruins, we wondered: How can the world allow Israel to destroy houses so old with carvings made by the hands of the grandfathers of the grandfathers of the people living there

These old stones, smelling of ancient traditions and modern destruction and abusive military power, are carefully preserved by some of the southerners. The reason? To rebuild their houses with these very same stones and their memories. The people here are holding on to their way of life and their history with a tenacity unparalleled in a fast-paced, emotionally-void hi-tech world

These old houses in the South were not constructed, they were created. They were created by warm human hands dreaming of simple domesticity, dreaming of warmth in the winter and of family gatherings. They were built in a time when the human mind had not yet outdone the devil

They were built with dreams of growing old and sitting on the porch with a dozen grandchildren playing beneath the orange trees. They were built with hands roughened by the stones, nails cracked, the dirt of the earth underneath them. They were created so that the warm homey smells of wild mountain thyme and olive oil could waft out of the kitchen windows. They were built for drinking hot coffee with the neighbors in the chilly afternoons in the mountains

They were built so that sons and daughters could get married and could settle down, starting their own families, continuing the traditions of the fathers, but starting their own dreams, lives, and loves

They were created from love, and through love their current owners aim to preserve them. They were created from dreams and in dreams they will remain

Journalists and historians will not write about these houses or the people who lived in them. History books will only remember the numbers, not the lives or the dreams. Reports and accounts will speak only of the bombs, the policies, the armies, the press conferences and the resolutions. The memories of the ways of the South, will however, continue to live in the hearts of its people and of those who love them

*This line refers to Bint Jbeil in a folk poem offering salutation to each of the southern villages

The articles posted on this site represent the opinions of their authors. Dar Al Amir does not necessarily endorse them |